Today’s migratory routes are often marked by crossings of seas and deserts, which for many, too many people — too many! — are deadly.

Pope Francis, 2024

As of June 2024, 122.6 million people were forcibly displaced, of which 43.7 million people are refugees[1].

People are forcibly displaced for a number of reasons, including persecution, conflict and human rights violations. Some may be able to relocate within the same country, identifying them as an internally displaced person (IDP), whereas others may be forced to flee their country of origin and travel to neighbouring countries in search of safety.

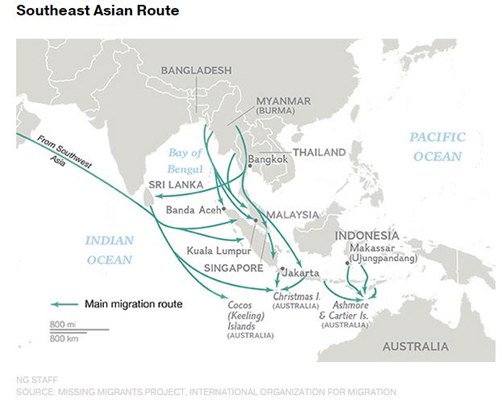

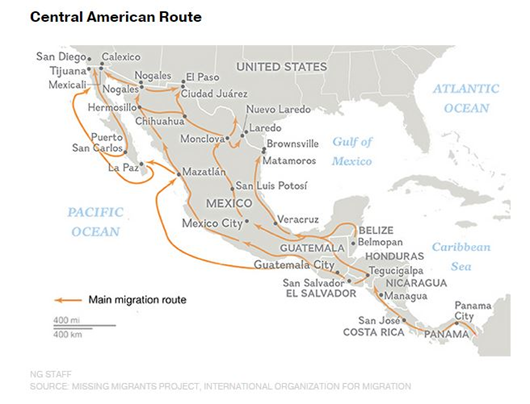

There are a number of migratory routes across the globe which individuals and families take in search of refuge, may be smuggled across, or may even trafficked along by gangs. These routes are ever-shifting and can be quite dangerous, passing through dessert, rough seas and violent borders.

There are currently a number of ongoing crises in the world, resulting in forcibly displaced people and increasing numbers of refugees. There is a misconception that all refugees want to travel to Europe, and that all are trying to seek asylum in the UK. Research shows that most refugees stay in countries neighbouring their country of origin, and it is these countries that host the majority of the world’s forcibly displaced which includes refugees and individuals in need of international protection, as well as stateless people.

UNHCR’s figures as of mid-2024, show the following[2]:

65% of refugees and people in need of international protection originate from just four countries:

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Venezuela

- Ukraine

- Afghanistan

32% of refugees and people in need of international protection are hosted in 5 countries:

- Islamic Republic of Iran

- Türkiye

- Colombia

- Germany

- Uganda

69% of refugees and people in need of international protection are hosted in countries neighbouring their country of origin, with 71% being hosted in low- and middle-income countries.

Those who travel onwards do so because of safety concerns in neighbouring countries, lack of support or in order to reunite with family members in other parts of the world. These journeys are often arduous and perilous, but people embark on them in the hopes of finding safety and of a better life.

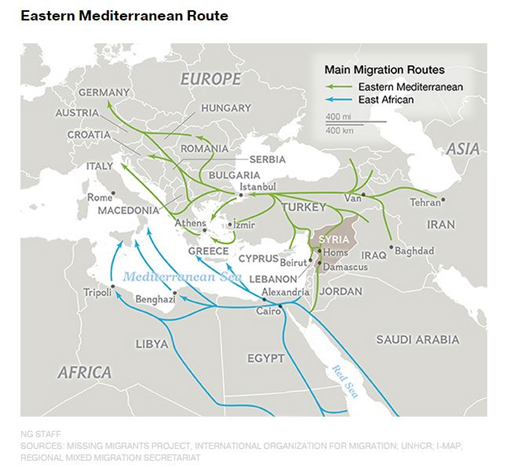

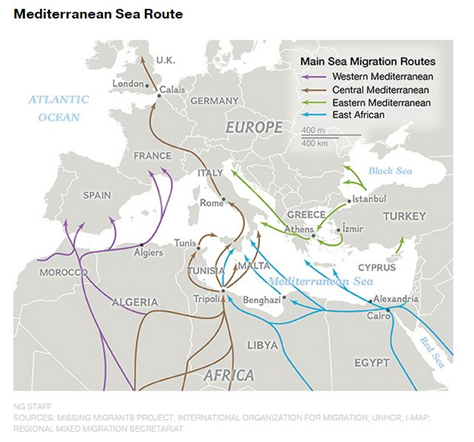

In order to understand the need for safe routes, it is important to understand the many migratory routes currently in use. Migration routes are complex and can be multi-directional. It is important to note that these routes are used by refugees, smuggled migrants and human trafficking victims, each with their own reasons for flight and onward movement. The following are four maps[3] of current migration routes around the world, each one serving different populations of forcibly displaced people. These maps illustrate the many routes taken across multiple countries, through vast deserts such as the Sahara, and the various sea crossings.

These irregular routes are born of necessary detours due to increasingly harsh border policies. People make their way along these routes without any form of support or resources, sometimes hiring smugglers and sometimes exploited by traffickers who station themselves purposefully along migratory routes to target vulnerable individuals and extort them for thousands of pounds, whilst subjecting them to extreme torture and abuse.

The Central Mediterranean Route is one of the biggest, and deadliest, migration routes in the world[4]. Pope Francis referred to the Mediterranean Sea as a ‘graveyard of dignity’[5] and warned leaders to not let it become a ‘cemetery for migrants’[6] – similarly mass graves have been found in the Sahara desert, with some arguing the desert may now be more deadly than the sea[7]. The Sahara desert is major transit route and there are reported crimes of ‘human trafficking, torture, forced labour, extortion, starvation, detention and mass expulsions’[8], all of which contribute to the deaths of many vulnerable people as they seek refuge.

There is a noted lack of access to protection and humanitarian assistance along these key routes, further exposing people to exploitation by gangs and traffickers[9]. However, individuals continue to make these journeys due to a lack of alternatives and a lack of safe routes which would allow them to apply for asylum in Europe and to reunite with family members already settled there, without having to make such journeys.

Channel Crossings

Channel crossings refer to small boats crossing the English Channel, from France to England. 2024 is noted to be the deadliest year on record for Channel crossings. According to the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Missing Migrants Project, at least 82 people, including 14 children, died trying to cross the Channel in 2024[10].

Both the French and UK Government have chosen to pursue a policy of securitisation, intensifying patrols and intercepting small boats. Both governments argue that they are targeting smuggling gangs. However, vulnerable refugees are the ones suffering as smugglers increasingly take more riskier routes and cram more people into one boat to evade detection and also force refugees to steer the boats to evade capture themselves. Smugglers are not deterred by these changes in policy and security tactics – they adapt their business models, and the refugees are the ones who suffer and ultimately lose their lives in the Channel as there is no alternative route available.

The increase in security and enforcement to ‘stop the boats’ and ‘smash the gangs’ has arguably resulted in the increase in deaths in the Channel, which the Refugee Council notes the Home Office accepted in September 2024[11]. Further, in November 2024 the Minister of state for Border Security & Asylum, told the House of Commons that “[t]he loss of life in the Channel this year has been the highest on record, and that is because more pressure is being put on the gangs, the boats are being overloaded and there is more anarchy on the beaches in France.”[12] However, regardless of this recognition, there is no plan by the Government to mitigate the risk, nor to introduce safe and ‘legal’ alternatives to Channel crossings.

The Government does not publish any official data confirming the number of deaths, nor information about the people who die. The Refugee Council argues that the lack of data on Channel deaths leads to an evidence gap as to how people die and why they were trying to reach the UK, all of which could contribute to better policy making[13].

The Diocese of Westminster Justice & Peace Commission, together with The London Catholic Worker, and London Churches Refugee Fund organise a prayer vigil on the third Monday of each month to raise awareness and pray for those who have lost their lives, reading out a list of names of those who have died. All are welcome to join.

Address: 2 Marsham St, London SW1P 4DF.

[1] https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/refugees#:~:text=At%20the%20end%20of%20June%202024%2C%20122.6,displaced%20people%20and%208%20million%20asylum%20seekers.

[2] https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics

[3] https://weblog.iom.int/worlds-congested-human-migration-routes-5-maps

[4] https://www.unicef.ch/en/current/blog/2024-06-19/world-refugee-day-biggest-migration-routes-world

[5] https://www.ewtnvatican.com/articles/pope-francis-calls-for-compassion-and-unity-in-the-face-of-mediterranean-tragedy-1574

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/world/stop-mediterranean-becoming-vast-migrant-cemetery-pope-tells-europe-idUSKCN0J9112/

[7] https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/58339/un-discovers-mass-grave-of-migrants-along-libyatunisia-border

[8] https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/58339/un-discovers-mass-grave-of-migrants-along-libyatunisia-border

[9] https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/09/1155176

[10] https://missingmigrants.iom.int/

[11] https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/stay-informed/statistics-and-research/deaths-in-the-channel-what-needs-to-change/

[12] https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2024-11-06/debates/77B1E99D-C873-49E1-9EB9-B6F57C0B939C/details

[13] https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/stay-informed/statistics-and-research/deaths-in-the-channel-what-needs-to-change/

You must be logged in to post a comment.