Clive Chapman, Director of Mission, CSAN

St Mary’s University, Twickenham, organised a Study Day on 26 January 2022, marking 25 years since the publication of ‘The Common Good and the Catholic Church’s Social Teaching’ by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. Technological advances since then made it possible for me to join the formal proceedings virtually, though social engagement space on this occasion was limited to those present physically in London. It was a great delight that CSAN and Catholic charities were much in evidence at the event; my own CEO, Raymond Friel, gave one of the speeches.

This was for me an anniversary celebration tinged with a little lament: what appeared to have been the principal public discussion on a Church document aimed at wider and deeper civic engagement, had become an academic matter, centred on leafy South-West London. Was this in itself a sign that voices from ‘the margins’, notably absent in the original document, were no more central to institutional discourse on Catholic public voice today? The day was, however, what it said ‘on the tin’, a study day – and quite reasonably an opportunity to promote higher studies. On another level, the university could be seen here taking on a role as a repository of professional knowledge – how such documents are developed, the challenges and how these are addressed, and why these documents are unusual/infrequent. This long view and experience is in short supply for work needed to form ‘concrete demands’ of Catholic domestic social action today, revealed particularly in the ongoing challenge of securing support for even basic national infrastructure, and levels of participation by Catholics under the age of around 50. The university setting was perhaps fitting for an independent critique of practice, but it would have been good to hear more from current practitioners on the state of current practice.

Why has it taken 25 years for the knowledge accrued by those working in 1996-97 to be transferred to today’s practitioners? Clifford Longley, the document’s author, revealed that he had been under a duty of confidentiality at the time, in his relationship with the Bishops’ Conference. He was now in a position to share some insights on the editorial, ecclesial and political contexts for the relative success of the document.

Pat Jones, the sole woman on the editorial group at the time, highlighted the unease and urgency that propelled action and eventual unanimous support for the document from the bishops in England and Wales (though not, as Clifford noted, without a backlash from the bishops in Scotland). However, she noted too the absence of experience of Catholic charities such as those in membership of CSAN. On reflection, the document now seemed to her cautious and moderate, perhaps reflecting the tone of global Catholic voice at the time on social concerns, and with relatively little reference to Scripture compared for example to Fratelli tutti.

For Clifford and Jon Cruddas MP, the document was timely, capturing the zeitgeist of a moment at which the impact of policies of a long Conservative administration (within wider forces of globalisation and distortions of capitalism) came under more intense questioning. Jon summarised a sense that public policy had been dominated by a ‘winner takes all’ approach to outcomes.

Pat pinpointed some of the challenges for the work of forming a Catholic public voice, both within Catholic ecclesiology and the messy process of dialogue in which the Spirit is active. An emphasis in the tradition on the see-judge-act/social action of individuals downplays the sociality of faith and importance of collective representation that are also characteristically Catholic. Pat praised the contributions of Catholic charities in innovating, expanding and discerning, but their collective impact was falling short on account of fragmentation. There remained insufficient infrastructure capacity to resource parishes to develop civic engagement. Pat helpfully challenged us all that without more attention to supporting these conversations, Catholics could struggle to make much more progress together as credible agents of change alongside others’ efforts. Francis Davis went further, in a withering assessment of most diocesan annual reports, that suggested to him a low priority in their structures and spending on the preferential option for the poor. I think that assessment failed to acknowledge the voluntary nature of most Catholic social action on the ground, which is also led in the main by women.

Pat also took issue with the lack of courage in some official statements – a dodging of the ‘concrete demand’ by staying in the comfortable realm of broad principles, while others had called for very specific policy changes (typically on issues overseas). Pat sensed that the focus of Catholic voice on domestic social concerns in recent years ‘has turned inward while people are suffering’, for example in social care; a national Catholic voice on social security reform is a particular gap. For Pat, this comes down in large part to how well policy work is resourced in national Catholic offices. This is one factor, but the relative energy directed into environmental and migration concerns in recent years, along with the research CSAN has sponsored on Catholic parishioners’ attitudes to social care, tell a different story about what is possible when the voices of religious congregations and a plenary resolution from the bishops are followed through into fresh action locally. As Pat noted, many of the bishops’ most powerful and specific statements were only possible because there was a policy specialist retained in the Conference to put them together.

Several speakers noted important Appendices to the document, ‘Catholic Resources’ listing examples of Catholic organised action, and suggestions to help discussion of the document in parishes. Raymond highlighted the priority for CSAN of gathering and communicating the story of Catholic social action today.

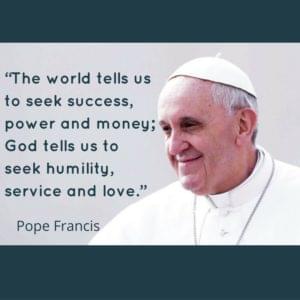

Bishop Richard Moth, Chair of the Department for Social Justice in the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, concluded the day by starting with a wide view. He recalled the enactment of Catholic social teaching over the last two centuries; the role of the Catholic Church in founding schools for the poor in the 19th Century; the quiet work of visiting people experiencing isolation undertaken by the SVP; the work of organisations such as Pact and the National Board of Catholic Women, and Catholic involvement in starting housing associations and credit unions. He emphasised the root of social action in the interior life and on the person of Christ. Without this rooting, social action becomes prone to pride and a distorted sense of service. He gave a great example of one man’s initiative and organising to help save a local market that would otherwise have been lost: the central place of local action.

Bishop Moth considered that there had been significant progress in bringing the fruits of Catholic thought and action into a positive influence on public affairs.

This blog post is not a statement of CSAN policy.